Wednesday was the first day of a new era of online protections for kids. The Age Appropriate Design Code became law in the UK, impacting companies around the world. Any website, app, or digital service with users or operations in the UK will now have to consider the best interests of their under-18 audience in designing their services.

(To see how it may apply to you, check out our earlier analysis or the ICO’s excellent code of practice.)

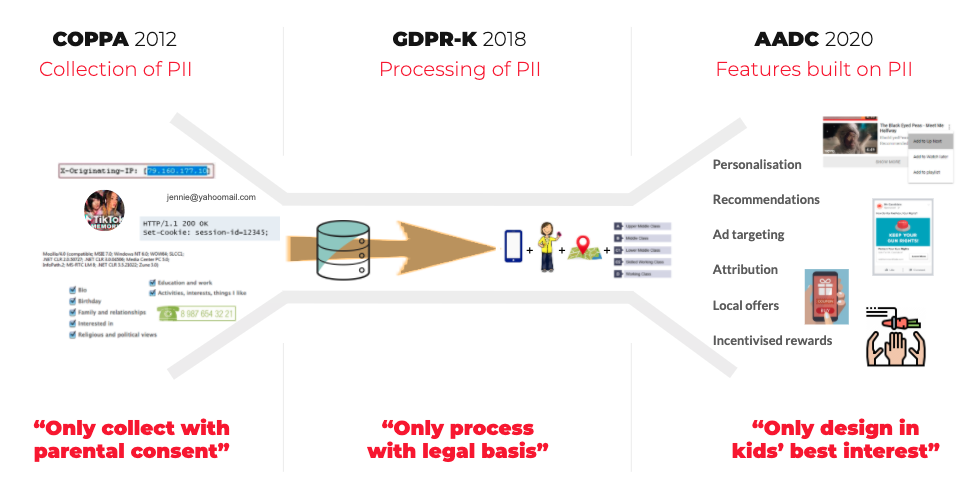

The Children’s Code represents a sea change in the scope of data privacy laws.

In 2013, COPPA reinvented personal data to include technical identifiers, swiftly putting all internet transactions with kids under scrutiny. In 2018, the GDPR established that what matters is how we process data, and introduced the world to the simple principle that now underpins all new data privacy laws: minimising the use of personal data.

And now, in 2020, the Children’s Code directly tackles the often pernicious use of personal data to manipulate consumer behaviour. Coincidentally, on the same day the Code became law, the FTC announced a settlement with kids’ app ABCmouse that makes a great case study for why the Code is needed. In a separate statement, FTC Commissioner Chopra summarised the issue bluntly:

“Companies have also used dark patterns to manipulate users about privacy settings… From making ads look like organic search results to creating a maze of ‘privacy’ settings so complex that their own engineers and employees can’t crack the code…”

The Children’s Code calls these types of dark patterns ‘nudge techniques’ (standard 13) and explicitly prohibits their use to encourage kids to share personal data, or make it hard to configure their privacy settings. This standard is reinforced by the requirement to default to maximum privacy settings (7), to avoid collecting geolocation (10), and to avoid profiling children for marketing purposes (12).

In what is perhaps its most far-reaching standard (5), the Code explicitly prohibits the detrimental use of data, including for advertising that breaches CAP Code rules. This directly challenges operators who use common techniques to extend engagement—from auto-play to personalised recommendations to reward loops—in a way that may cause harm to children. And it undoubtedly doubles the pressure on games developers to wean themselves off highly profitable but controversial features such as loot boxes, which are now under pressure from politicians and regulators in multiple countries, including the US (see the recent class action lawsuit against a game developer for a thorough overview of these actions).

Operators have one year to rethink their approach to kids through the lens of the Code. Although launched in the UK, we expect its standards to influence regulation and best practice around the world in the coming years.

For more on how UK Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham sees the Code influencing app design going forward, listen to this #Kidtech podcast interview released yesterday.